Me-Mom: Tanujaa Rane

Tanujaa Rane is a printmaker, who has pursued the technique of etching today with a meticulousness that is rare in today’s world of art production.

Printmaking is a subject that several artists take up while in art school, but the continued practice is now somewhat rare. Making of prints is time-consuming; it can be expensive and laborious. In India the concept of having studios where specialized printmakers help the artists to produce limited edition, hand-pulled editions, is also unknown. A hand-cranked printing press takes up studio space that one might not have to spare. All these combined factors make the medium a rarity in the art world of contemporary India.

Tanujaa faces all the travails mentioned above, but continues to makes etchings despite that. Although prints need to fit into a fixed paper size that a machine is able to take, Tanujaa extends her imagery way beyond that. She is ambitious in scale, and makes prints that extend into 4 parts, 8 parts and even 16 parts. The imagery moves from one sheet of paper into another, extending the story, constructing panels and grids that lead the eye from one onto another.

In the current body of work, titled, Me-Mom, Tanujaa becomes the narrator of stories, of myths, and of legends from the past to her new-born son. But she also becomes the one affected by the depth of cosmic power that his presence awakens in her. Stories of leadership, of good vs bad, and of assiduousness are told through popular tales. Her son listens intently and wisely, but is the all-knowing from another world.

Tanujaa seizes on what is a precious time: before her son begins speaking. From then the dialogue will be moved into the realm of questions and answers, questions of the details of the world, questions that will cloud the directness and transcendence of fables and myths.

In Pink Horse, the story begins with the audacities and inextricable dark sides of life being juxtaposed with the plush comforts of childhood. On one side of the piece: a stuffed pink horse, on the other, its counterpart on the battlefield. The plush source of comfort becomes the harbinger of destruction: a blotted out image of a horse in battle pulling the chariot of Krishna and Arjuna into battle. The piece functions to introduce her new-born son to the absurdity of destruction in the world: in sharp focus are insects battling to a senseless death not for food but for hate, a battle continually mirrored in the wars of human history. But on closer inspection the viewer finds the image of Krishna, the divine authority, guiding the seeming chaos. We can imagine this baby-boy, this angel from another world, clutching his comfortable plaything as he slowly becomes aware of its role too in the ugliness of the world, but a world none the less ruled by the laws of the divine.

The limits of our knowledge are approached in Dinosaur, where Tanujaa communicates to her son a multifaceted meaning: the need for imagination, and the fleeting manner of our existence. In a sense she wishes to tell a very straightforward story: these huge reptiles roamed the earth millions of years before we did. But she also seeks to communicate something else: what do we really know of this time? All we have left is bones from an entire world that came before us, and from these bones imagination has brought to life an entire story of which we have no real knowledge. She seeks to communicate the poetry and wonder of such a situation.

In Lion Emperor, she speaks of leadership. Seated in an old carved South Indian Maharaja’s chair sits a stoic lion, above him, a crown floats in the air. In a world of Prime Ministers, Legislators, Parliaments, and Presidents, instead of Maharaja’s and Kings, the crown will no longer be worn. The crown exists, but it is no ones to posses.

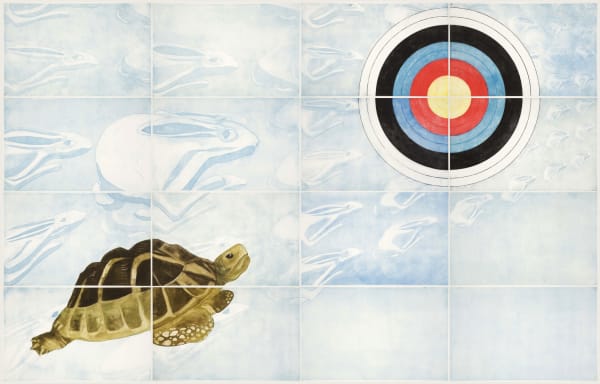

In Target, Tanujaa revisits the familiar tale of the tortoise and the hare, and a lesson in discipline and patience emerges. The hares, in their haste, loose their forms, disappearing into clouds. They appear everywhere, but touch one and they vanish. Their eyes look back at the detailed image of the tortoise, worried for what lies behind them, and in their fury they miss the colourful, opaque target, flying beyond where they set out to reach.

The last two pieces in the series, Me-Mom and He-Dad, have evolved from doing the work itself. They speak to the difficulty of living up to our own expectations of ourselves; of the mechanizations of the artists own emotions, and her yearnings to return to time spent out of time with her son. It speaks of her own misgivings of her life becoming too robotic, special moments and special feelings shared with her son being brushed aside in the name of getting her work done. She realizes in time, that in narrating these tales, she the mother, and her husband, the father, (Me-Mom and He-Dad) become mechanized receptacles of events of the past. He Dad carries on him a powerful tool that exists outside the definition of weapon or magic wand, but as some sort of manifestation of the power of the head of the family: representing his seemingly magical powers to protect and to make wishes come true.

Tanujaa looks ironically at her role as a parent through the stories she tells. The legends carry their own satire, where the all-powerful lion awaits his crown, the racing hares “miss the point”, the transformation of the horse from the battlefield to soft-toy. The “all knowing parent” gets reduced to a robot looking to her newborn for wisdom and clarity. Her son is the star that comes from a very different world - a cosmic world of abstraction and creativity and carries with him the universe within.

It is now her turn to listen to him.